Dyspraxia / DCD, Fine Motor Skills

Is Clumsiness a Sign of ADHD

A paediatricians guide to address sensory and motor skills disorders for parents

Have you ever glanced at your child and wondered why they struggle with activities such as jumping, running, catching or throwing a ball? Is clumsiness a sign of ADHD or perhaps they struggle with handwriting, using scissors, or using eating utensils. In this article, we discuss coordination in children and when you as a parent should seek the necessary help for your child to help them get through their coordination difficulty.

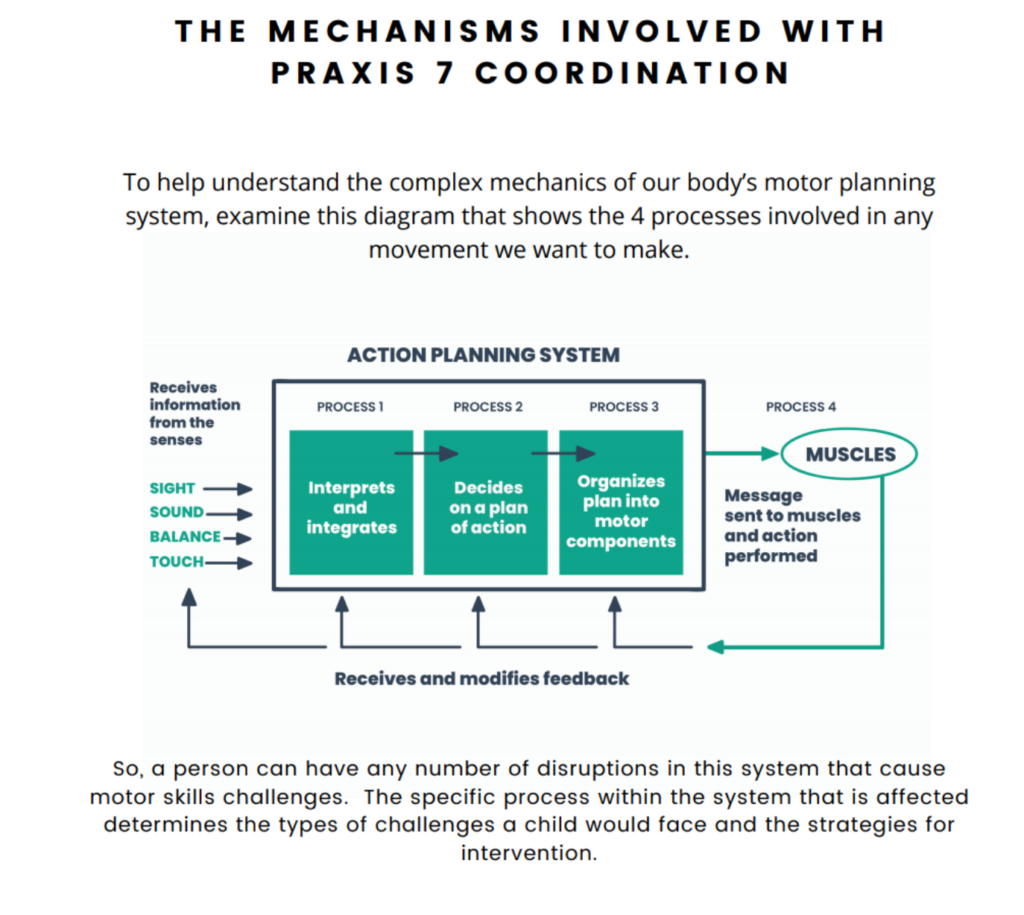

All parents want to see their children succeed in life. With the help of a paediatric occupational therapist, they can determine the exact origin where the child has the most difficulty, which is called an activity analysis. There are certain building blocks a child needs to reach in order to develop balance and coordination. Some include but are not limited to attention and concentration, hand-eye coordination, postural control and self-regulation.

Have you thought of Development Coordination Disorder (DCD) aka Dyspraxia?

It is believed that 60% of children show some of the signs of dyspraxia which could originate from neurological medical conditions such as brain injuries, seizures, hypothyroidism and a vitamin E deficiency. All of the above can affect a child’s coordination. However, sensory processing disorder can also be another factor that affects coordination in children. If left untreated, it could make daily activities increasingly difficult for both the child and the parents.

Coordination is truly a spectrum, just like many things. There are some people with incredible balance that can dance and flip atop a balance beam. And there are those with “two left feet” and hate to dance on the stable ground, let alone a balance beam!

But there are some children who are truly uncoordinated and struggle with everyday tasks. So, if your little one spills every time they pour a drink, falls down regularly when playing, bumps into furniture, or slips down stairs… you might be wondering when to worry about a child’s clumsiness.

An Important Note: There are many reasons why a child could seem overly clumsy, so it is important to work with your child’s paediatrician to get a full medical history and family history. Brain injuries, seizures, even things like vitamin E deficiency or hypothyroidism can affect a person’s coordination.

But my focus in this discussion is on children with no apparent medical reason to exhibit floppiness, clumsiness, and disorganisation – in both movement and mental organisation.

As a paediatric occupational therapist who specialises in sensory and motor skills disorders, I’ve spent my career helping parents identify and understand a variety of conditions that affect motor skills and present as child clumsiness symptoms.

There are several different developmental disorders that can all affect a child’s motor skills and subsequently dexterity and coordination. Dyspraxia and developmental coordination disorder, for examples, are neurological conditions that present symptoms often described as clumsy movements.

Sensory processing disorder is another that affects a child’s coordination. Researchers believe that anywhere from 6-10 percent of children today show some of the signs of dyspraxia.

Plus, it’s an unseen condition that can present in children with ADHD, adding a layer of difficulty to their daily life.

So, What’s the Easy Answer for When to Worry About Child Clumsiness?

If any of these scenarios rings true for your child, I would encourage you to seek professional evaluation of your child’s specific symptoms and get an answer if clumsiness is a sign of ADHD.

- They struggle with everyday tasks.

- They have meltdowns every day. (There’s a difference between a meltdown and a tantrum. Read more.)

- They are starting to avoid situations or tasks that should be fun or simple to accomplish.

- They’re getting physically hurt or physically hurting other people by playing too rough or seeming aggressive.

- Their ability to make friends and enjoy social interactions is affected negatively.

- They are failing at school work, even though they’re truly a smart child.

Rather than discussing some of these challenges from a broad perspective, I thought it might be useful to offer a specific example from my experience working with clumsy children and to find out if clumsiness is a sign of ADHD

This might help parents worrying when to worry about their own child’s clumsiness by seeing the wide range of affects discoordination can have on a child’s day-to-day life..

Use our Dyspraxia Symptoms Checklist of common dyspraxia “clumsiness” symptoms to start a Sensory Profile that you can discuss with your pediatrician.

A Clumsy Child’s Case Study: Will My Child Ever Be Able to Ride a Bike?

For a child with a motor coordination disorder, riding a bicycle is often an early hurdle that seems hopeless. Bikes and cycling have become synonymous with childhood.

Most adults can recall the times that they were racing on bikes with their friends. Despite falls and minor injuries, most adults think about these times as some of the best times that they have spent with friends.

But for a child with poor coordination, a bicycle represents many levels of complex coordination. And falling is humiliating to a child. It registers deep within as negative feedback attached to the experience, both physical and emotional.

Difficulties with processing movement sensations creates problems with sensory-motor skills such as balance, muscle tone, posture, and gross motor coordination.

The underlying issue would be poor processing of movement sensations and/or gravitational insecurity.

The latter means that the person becomes anxious when the feet do not have contact with a stable surface such as a floor. Rhythm and sequential movements are also affected.

All of these skills are needed to ride a bike. You need to balance, to have adequate muscle tone and muscle strength to pedal; you need to maintain a stable posture and you need coordinated movements. When pedaling you use rhythm and sequenced movements.

The two sides of the body also have to work together in a coordinated way to ensure smooth pedaling. If a child has problems with one or more of these areas, he or she will either look awkward or it will be impossible for the child to ride a bike.

Meet Johnny

Let me introduce you to Johnny. I met Johnny when he was 8 years old. Johnny had many issues with handwriting and spelling in school.

His teacher recommended an occupational therapy assessment and a test to identify possible dyslexia. Belinda, a single mum, was concerned about her son’s progress in school.

Johnny had been a happy baby with good sleeping habits and no feeding problems. During his pre-school years he seemed a bit clumsy- falling over his own feet- but he did well in the classroom, and Belinda simply accepted that he might never be a good sportsman.

Johnny often wrote his name in reverse (i.e. mirror image) and found it difficult to memorize words. In Year 1 he kept up with schoolwork, although spelling was a problem. Johnny was slow to learn to skip and to do star jumps. Ball skills were at a low average, and he avoided all sport at home and at school.

Physically he looked slightly overweight, walked at a slow pace, and came across as inactive. He liked being on the swings at the park, but he was dependent on Belinda to swing him – he could not do this by himself.

He claimed that he didn’t want a bike, yet Belinda confirmed that he had a bike but found it difficult learning to ride it. He gave up trying to ride and did not seem to have the will power to practise. This concerned Belinda.

Johnny’s Assessment Results

The assessment results indicated that Johnny had problems with balance, bilateral integration, and sequencing. His scores for these sub-tests were significantly lower than the average expected for his age group.

The rest of the assessment scored above average for his age. Thus, there was a huge difference between these skills and his other abilities. Differences in skills and/or performance usually create some form of anxiety in the child and of course avoidance of the tasks that the child finds challenging.

Therapy focused on bilateral integration and sequencing with activities called “brain bridging”. Johnny was reluctant to participate in some exercises that included ball games.

We then started with exercises that he found very easy and gradually increased the complexity of these exercises to make him feel more in control of his body and to ensure positive feedback from such experiences.

Within a number of weeks Johnny’s abilities improved to such an extent that he was eager to try unfamiliar games. Belinda reported one day that she didn’t recognise him when he came running towards her amongst a group of children at school pick up time! Never before had she realized that she identified him by his clumsy running style.

Now that he was running with coordinated movements, he didn’t stand out in the group anymore. Around this phase of intervention, we started to include activities that involve movement equipment and challenge the balance mechanism in our body.

This was to make him aware of his improved skills and also to give him the self-confidence to attempt riding his bike once again. Two weeks later he came in with good news – they went to a park over the week-end, took the bike along and he rode off!

Belinda reported that it was one of the most amazing experiences to see this boy riding. He returned to her with shiny eyes, big smiles, and pure enjoyment on his face. In therapy the focus shifted to two dimensional tasks such as writing and spelling.

The recognition of left and right on his body was well established but he had to understand this concept on paper to minimize reversals of letters and numbers. For the first time in his life, Johnny was able to recite and write the alphabet without hesitation and without support such as a song – sequencing was certainly well-developed on all levels.

During the school holidays Johnny attended his last few therapy sessions. He introduced me to one of his friends who came along. They were excited as they planned a bike ride with another group in the park after therapy.

Johnny was also ready to participate in martial arts with his friends. I saw Belinda in a shop a few months later. She told me how active Johnny was, that he lost weight and that he excelled in martial arts.

In school he was coping well with tutoring to ensure that the foundation of reading, spelling and mathematics was firmly established.

Inadequate sensory-motor skills and specifically bilateral integration and sequencing made it difficult for Johnny to cope in most aspects of his life. Once these foundational skills were developed as expected for his age, he could participate successfully in all the games that his friends enjoyed. And he could use his bike with ease and enjoyment.

View Marga’s Lecture: Sensory Motor Skills

Understanding the Full SpectrumClick here to purchase

Read More Stories Like You Just Read

From Marga’s Book, “Stories of Hope” Available on Amazon

Pingback: Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (Dyspraxia)